Lack of sleep linked to glucose insensitivity and pre-diabetes | Matthew Walker

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The BDNF Protocol Guide

An essential checklist for cognitive longevity — filled with specific exercise, heat stress, and omega-3 protocols for boosting BDNF. Enter your email, and we'll deliver it straight to your inbox.

Sleep quality is inherently linked to glucose metabolism. Epidemiological studies have shown that people who have poor sleep are at greater risk of having or developing diabetes. When a person does not get enough sleep, their pancreatic beta cells become less sensitive to glucose signaling, reducing the amount of insulin produced by the pancreas. This, in turn, impairs glucose uptake, resulting in hyperglycemia, a hallmark of diabetes. In this clip, Dr. Matthew Walker explains how sleep deprivation impairs glucose metabolism, increasing the risk of diabetes and metabolic dysfunction.

Rhonda: So let's talk about your, because a lot of interesting research has come out of your lab on the blood glucose regulation front and, well, I guess more on the eating preferences...

Matt: And appetite and eating.

Rhonda: ...and appetite. Yeah.

Matt: I mean, the way I see it, it's all part of the energy intake expenditure system. And sleep, you know, if you think about like a weighing scale between sort of energy expenditure and energy consumption, sleep, if you're not getting it, just annihilates that balance. And we can speak about any one of those things.

But, you know, I think the blood glucose story and sleep is very very well-worked out now. It started with epidemiological studies, where we started to see that people who were sleeping less than seven hours were at significantly higher likelihood of either being diabetic or going on to develop diabetes. Many of them were already, you know, what we call a pre-diabetic state, or they had what we now call sort of metabolic disorder.

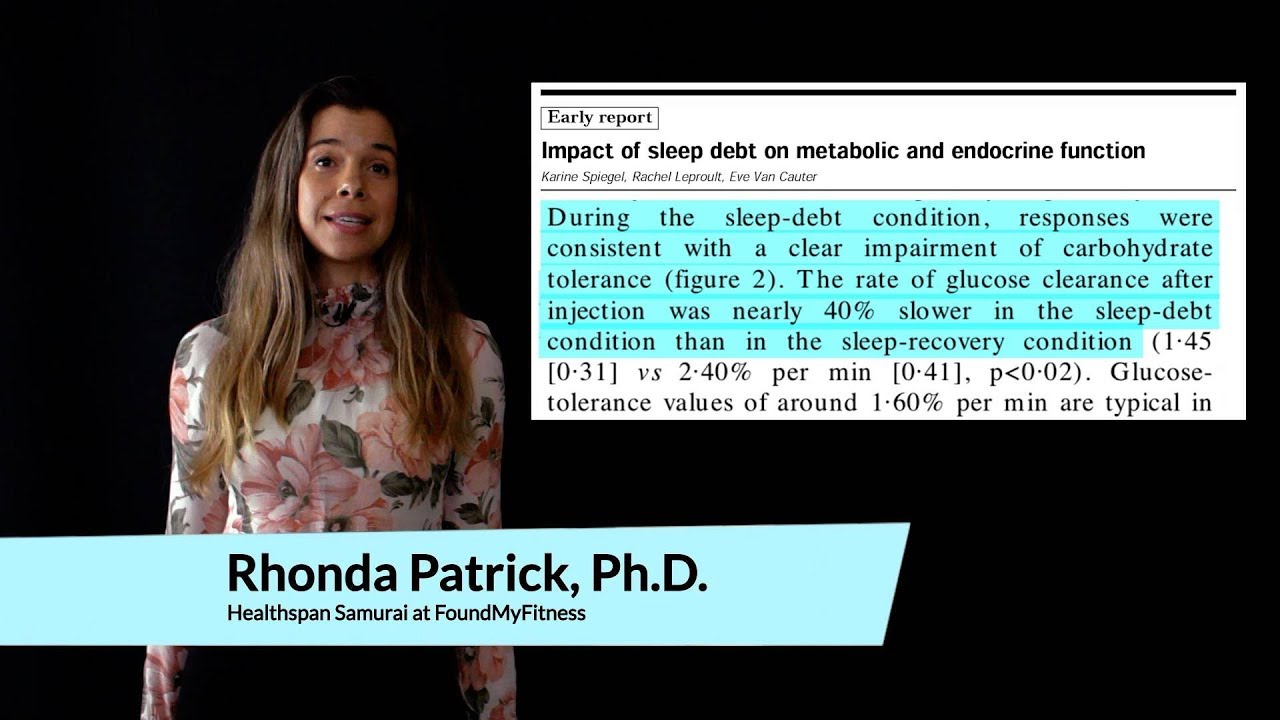

And then the question became, well, is that associational or is it causal? So the next studies that happened in this was work back in...starts in the 1990s by Eve Van Carter at the University of Chicago. Wonderful studies. It took a group of healthy people, started to limit them to different doses of sleep for a week, you know, five hours of sleep, six hours of sleep, four hours of sleep, and what she showed was that, essentially, after one week of short sleep, your blood sugar levels are disrupted so significantly that your doctor would classify you at that point as being pre-diabetic after one week of short sleep.

And the way that they do this is what's called a glucose tolerance test, where you are fasted, and then you are given this sickly-sweet drink of glucose, and then they are measuring from your blood in the next three or four hours how quickly is your body able to dispose of that blood glucose.

So what happens when you drink or when you eat a meal is that your blood sugar spikes. And you don't want that spike to stick around very long. If your body is healthy, it deals with that raised level of blood glucose very quickly, and it brings it back down very quickly. That's a healthy profile. That's what we call good glucose management. So how good is your body at disposing essentially of that glucose? And the way it disposes it is that cells in the body, including muscle cells, will suck up that glucose. And it's called your disposal index, or your disposition index, it turns out.

So what she found, Eve Van Carter, with her studies, was that, firstly, the way that your body knows how to absorb glucose and suck in that glucose is that there is another chemical called insulin, which is released by the pancreas, beta cells of the pancreas, and that insulin will instruct the cells of the body to open up special glucose channels to absorb the glucose and your blood sugar drops, which is good and healthy.

Firstly, what she found was that when you are not getting sufficient sleep, the beta cells in your pancreas stop being sensitive to the signal of high glucose. So the beta cells, which normally are listening for this spike in glucose, and as soon as they sort of, you know, hear...no, they're not hearing it. They're sensing it. But as soon as they sense the spike in glucose, they release insulin. And that insulin will drop your blood glucose.

But those cells had become insensitive to glucose, what we call sort of glucose insensitivity. And so the beta cells of the pancreas stopped releasing as much insulin. It didn't release enough insulin to drop blood glucose, so blood glucose remained high. If that wasn't bad enough, we've since gone on to demonstrate, and you can do this with really clever studies, taking tissue biopsies, the cells of the body including muscle cells and fat cells, their receptors stopped being as sensitive to insulin.

So, firstly, you're releasing less insulin when you're sleep-deprived. But what little insulin you do release is not instructing those cells to open up the channels to take away the monsoon of the glucose that's flowing in the channels of the body. So on both sides of the glucose regulation, on the release of insulin, to instruct cells to absorb glucose, and on those cells themselves to be sort of instructed by insulin, those cells became less sensitive to the insulin signal. And so, as a consequence, your overall ability to deal with glucose became far more degraded, and blood glucose remained higher, which sets you on a profile of looking pre-diabetic.

Rhonda: Couple that with the standard American diet, and, you know...

Matt: And you're off to the races in terms with...

Rhonda: Yeah, and eating late at night. So, actually, are you familiar with the studies, I know Dr. Satchin Panda actually is the one who told me about this, melatonin is actually what is responsible for shutting down the pancreatic beta islet cells from producing insulin. So I wonder how much of the sleep deprivation the melatonin system is involved in that.

Matt: Yeah. So in those studies, what was good is that they held constant circadian rhythms, they held constant ambient light, and they even held constant physical activity. The control group was sort of they were in bed for eight hours, but the people who are sleep deprived, limited to four or five hours, during the eight-hour window where the other people were actually sleeping, they had to lie recumbent in bed with no physical movement.

Rhonda: Oh, man.

Matt: So you controlled, but it was a great study because you control for physical activity as well. So we now really understand the link between a lack of sleep and poor glucose management, and very very well indeed. And we also know the stage of sleep that's important. It's, again, deep slow-wave sleep. The study that I described before, where you're playing those annoying tones just below the level of awakening so I can remove your deep quality of sleep, you can do that same thing again, and you essentially produce that same diabetic-like consequence just by removing or excising deep slow-wave sleep.

The body’s 24-hour cycles of biological, hormonal, and behavioral patterns. Circadian rhythms modulate a wide array of physiological processes, including the body’s production of hormones that regulate sleep, hunger, metabolism, and others, ultimately influencing body weight, performance, and susceptibility to disease. As much as 80 percent of gene expression in mammals is under circadian control, including genes in the brain, liver, and muscle.[1] Consequently, circadian rhythmicity may have profound implications for human healthspan.

- ^ Dkhissi-Benyahya, Ouria; Chang, Max; Mure, Ludovic S; Benegiamo, Giorgia; Panda, Satchidananda; Le, Hiep D., et al. (2018). Diurnal Transcriptome Atlas Of A Primate Across Major Neural And Peripheral Tissues Science 359, 6381.

A measure of the efficiency of a person’s glucose homeostasis. Disposition index is based on the ability of the beta cells to upregulate insulin secretion in response to a decrease in insulin sensitivity. It typically declines well before a person’s glucose levels rise into the diabetic range (126 mg/dL or greater). As such, a low disposition index is an early marker of poor beta-cell compensation and a risk factor for diabetes.

A peptide hormone secreted by the beta cells of the pancreatic islets cells. Insulin maintains normal blood glucose levels by facilitating the uptake of glucose into cells; regulating carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism; and promoting cell division and growth. Insulin resistance, a characteristic of type 2 diabetes, is a condition in which normal insulin levels do not produce a biological response, which can lead to high blood glucose levels.

A hormone that regulates the sleep-wake cycle in mammals. Melatonin is produced in the pineal gland of the brain and is involved in the expression of more than 500 genes. The greatest influence on melatonin secretion is light: Generally, melatonin levels are low during the day and high during the night. Interestingly, melatonin levels are elevated in blind people, potentially contributing to their decreased cancer risk.[1]

- ^ Feychting M; Osterlund B; Ahlbom A (1998). Reduced cancer incidence among the blind. Epidemiology 9, 5.

A test in which a person's glucose and sometimes insulin is tested before and at multiple intervals after having consumed a measured dose of glucose. Depending on the protocol, blood may be drawn for up to 6 hours afterward.

Clusters of cells found in the endocrine portion of the pancreas, an area also known as the islets of Langerhans. Pancreatic islet cells comprise three distinct cell types: Alpha cells, which secrete glucagon; beta cells, which secrete insulin; and delta cells, which secrete somatostatin.

A health condition in which blood glucose levels are higher than normal, but not high enough to indicate a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Prediabetes can be halted or reversed with dietary and lifestyle modifications, including weight loss, exercise, and stress reduction.

A metabolic disorder characterized by high blood sugar and insulin resistance. Type 2 diabetes is a progressive condition and is typically associated with overweight and low physical activity. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, unexplained weight loss, increased hunger, fatigue, and impaired healing. Long-term complications from poorly controlled type 2 diabetes include heart disease, stroke, diabetic retinopathy (and subsequent blindness), kidney failure, and diminished peripheral blood flow which may lead to amputations.

Member only extras:

Learn more about the advantages of a premium membership by clicking below.

Hear new content from Rhonda on The Aliquot, our member's only podcast

Listen in on our regularly curated interview segments called "Aliquots" released every week on our premium podcast The Aliquot. Aliquots come in two flavors: features and mashups.

- Hours of deep dive on topics like fasting, sauna, child development surfaced from our enormous collection of members-only Q&A episodes.

- Important conversational highlights from our interviews with extra commentary and value. Short but salient.

Sleep News

- Regular cannabis use during adolescence may be linked to long-term insomnia risk.

- People with insomnia benefit from regular mind-body or aerobic exercises, with yoga leading as the most effective—increasing total sleep time by nearly two hours.

- The air in children's sleeping areas harbors high chemical pollutant levels, potentially increasing young children's exposure to toxic compounds.

- Resistance training notably improves sleep quality in older adults, outperforming both aerobic and combined exercises.

- Sleep disruption reduces the newly discovered hormone 'raptin,' potentially increasing appetite and promoting weight gain.