Sauna Use for Depression: The Hyperthermia Protocol (Clinical Study)

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

The BDNF Protocol Guide

An essential checklist for cognitive longevity — filled with specific exercise, heat stress, and omega-3 protocols for boosting BDNF. Enter your email, and we'll deliver it straight to your inbox.

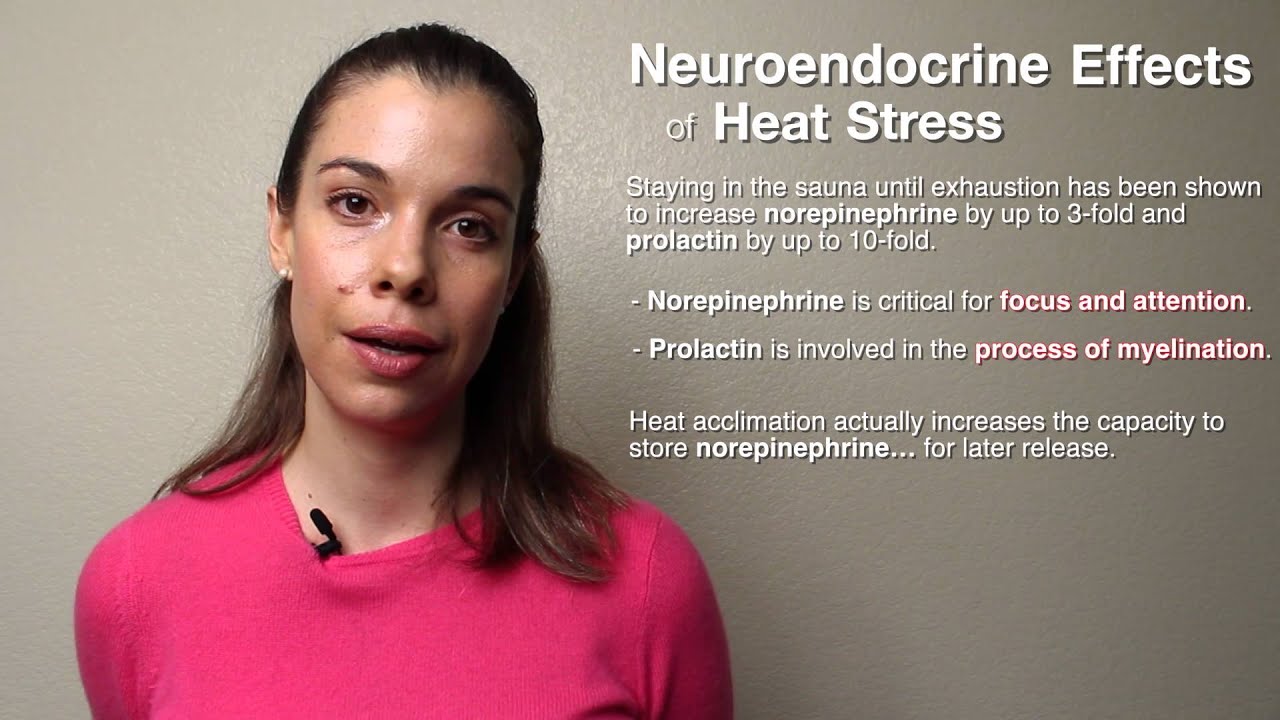

Whole-body hyperthermia is a therapeutic strategy used to treat a variety of medical conditions, including depression. Although whole-body hyperthermia and sauna use share some similarities, whole-body hyperthermia sessions are typically longer (an hour or more) and the participant's head is spared (often kept cool with ice or cool cloths), prolonging the participant's tolerance to the intense heat. Recent studies suggest that whole-body hyperthermia reduces symptoms of depression – with lasting effects. Some of these effects may be due to the way in which hyperthermia influences thermoregulatory function, which is often dysregulated in people who have depression.

Dr. Mason and her colleagues will further investigate the effects of whole-body hyperthermia on depression in a three-year-long trial – which she describes as the "ultimate mind-body intervention." They'll combine cognitive behavioral therapy with sauna use and measure inflammatory biomarkers (which are often elevated in people who have depression) to gauge the intervention's effects. Ultimately, Dr. Mason's goal is to identify sustainable, implementable strategies that help maintain wellness and help reduce symptoms of depression.

In this clip, Dr. Ashley Mason describes the differences between sauna use and whole-body hyperthermia; how the latter may be useful in treating people who have depression; and how a new trial will investigate its use.

Dr. Patrick: But whole-body hyperthermia is a new term for a lot of people, and it's a really important one because that is what, you know, clinically was used or is used to treat, or shown to help treat depression. Can you explain the nuance there with whole-body hyperthermia and how that's different from just going in the sauna?

Dr. Mason: Sure, sure. So it's an emerging field. And, like you said, a lot of people are familiar with sauna. It's at their gym, it's maybe even in their house, it's when they go on vacation. And going in the sauna and sweating and then leaving it is very pleasurable. It is often relaxing, calming. People enjoy doing it. They often report that they feel better afterward. Whole-body hyperthermia protocols are a little bit more intense. So if you ask someone who went into one of the saunas, in one of the studies that I'm sure we're going to talk about today, they might just not tell you it was a spa-like experience. It's very intense, there's a lot of sweating, and you get very, very hot. And, whereas with sauna, you might go in it for 15, 20 minutes, go out of the sauna to cool down for a bit, go back in. With whole-body hyperthermia protocols, you're getting heated pretty consistently for quite a while until you're on the other side and you're going to be done. It's not so much a going in and going out and going in process. And with whole-body hyperthermia protocols, especially in studies, there have been a lot more steps to control the experience than, say, going to a sauna at your gym. We can get into what some of those are if we want to talk about the specific studies. But they're pretty different experiences, although they both involve heat.

Dr. Patrick: And maybe, like, let's talk a little bit about some of the preliminary findings that got you interested in this research in the first place.

Dr. Mason: Yeah, absolutely. So in 2016, this paper came out by Janssen and a bunch of other co-authors where they reported on a whole-body hyperthermia protocol that they had used to test as a treatment for clinical depression. And this study was impressive for a number of reasons. They recruited 30-some-odd participants who had pretty significant depression. And they randomized half of them to get a whole-body hyperthermia treatment, or half of them to get a sham whole-body hyperthermia treatment. And I'm going to talk about what the differences are there in a second. But it was a very good idea for a placebo condition for this study. So the whole body hyperthermia condition, the folks randomized to receive this were put into a kind of whole-body hyperthermia machine that involved infrared heating lamps. And this is a pretty fancy machine. They run about $50,000. You only find them in hospitals. They're made in Germany. It's called a Heckel. And it's a pretty involved experience. So these people who were randomized to receive whole-body hyperthermia went into this sauna tent, if you will, the Heckel machine, and they were heated until they reached a core body temperature of 38.5 degrees Celsius. After that time, the sauna was turned off, and they stayed in there anyway for another hour just lying there. And during that time, their temperature actually continued to rise all the way up to about 38.85 or so degrees Celsius. And all during that time, they are sweating, sweating, sweating. They're hot. And what's really important to know about the sauna tent is that their head is outside of the sauna. So you asked about the differences between regular sauna and whole-body hyperthermia, this is a major one. When you go into a sauna, your whole body is going into the sauna, including your head. With these whole-body hyperthermia protocols, in many cases, your head is not in the heating element, it's outside of it. So you can be drinking, a person can be attending to your head, putting cool cloths on it, and so on, like they did in that Janssen study. Now, the other half of the people who didn't get the whole-body hyperthermia, they were actually put in that same machine, but it wasn't turned on to be very hot. And the lamps turned on, and they got a little bit warm, but they didn't get anywhere near as warm. I think it was like 99.5 degrees Fahrenheit that the control condition got into. And what's more is that the authors of the study actually asked all of the participants, "So what do you think you got? Do you think you got the real deal, the whole-body hyperthermia, or do you think you got the control condition?" Some 71% of people in that control condition thought they got the actual sauna treatment. So why is that exciting? Because when you actually look at the change in the depression scores for these people, it was pretty remarkable. The drops in depression within a week were pretty impressive. And what's more, those drops were maintained six weeks later. And this was one whole-body hyperthermia session. And so the difference between the groups was pretty notable six weeks out, and especially one week out. And this study caught my eye for a few reasons. One is that, as a whole, in this country, in many other countries, we're not just great at treating depression. It's a big problem. Antidepressants work for many people, therapy works for many people, but we still have a long way to go in developing treatments for depression. And when you see a treatment like that, with that strong of a control condition and those effect sizes and those reductions in depression, it catches your eye. So I got really excited about that, started looking more into, "Well, what else has been done with this?" And it turned out there was one other study in 2013, the Hanusch paper where they just recruited depressed participants, they gave them the sauna session, and then they looked at them afterward. And there are some really neat, striking findings about that study as well. But it was a single-arm study, because there was no control condition. But those two studies got me really excited and started me down this path, in particular with looking at temperature.

Dr. Patrick: There was a couple of things you said with, you know, Dr. Charles Raison's study, 2016 study, with this Heckel machine, this whole-body hyperthermia, that are really important. And those are that, one, you said that there was an effect within just a week of treatment, which is quite quickly. It's soon. I mean, like, if you think about classical, like, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, which are used very, you know, widely for, you know, depression treatment, they don't work that quick, they don't work immediately like that. So that was one thing, to get your thoughts. And, two, the fact that they did one session and it lasted six weeks. Like, they didn't have to keep going every day or even every week. I mean, they just did it once, and it was a six-week...like, there was a lasting effect. So what are your thoughts on...?

Dr. Mason: It was a big moment for me. And what I realized when I was thinking about that very SSRI thing was that, "Well, wait a minute, what do SSRIs have in common with all of this?" And I went back and I looked at some of the SSRI literature, and it turns out that one of the most common side effects of SSRIs is hyperhidrosis, it's sweating. So then I thought, "Huh, sweating one of the most common side effects of SSRIs. And yet, with whole-body hyperthermia, what are we actually doing? We should probably actually go back into some of the mechanisms a little bit here with this." But that really made me think, "Okay, wait a minute, do we have actual data now? Has anybody published on whether sweating in response to SSRIs is associated with if they're effective or not?" I'm actually not aware of a paper that has done that. It'd be a great paper and a great analysis to do. I hope someone is working on it. I'd love to work on it. There's a lot of data that we could use to test that. But getting back to your question about, wow, this works really fast. Yeah, SSRIs take weeks, can take months before they start to work, whereas Dr. Raison noticed these effects in just a week in his study design. And yes, they did last out to six weeks, and they didn't measure beyond six weeks. So we don't know what happened, and that's a key area of future research. But maybe we should talk a little bit about the hypothesis underlying why this might be working. And that's where my mind went after I saw that 2016 paper. I thought, "My goodness, what's going on here?" Well, it turns out there is literature showing temperature dysregulation in people with depression. Back early 1982 and then '97, a researcher, Dr. Avery published some work showing that people with depression often have higher nighttime body temperatures, and they're not as good at thermoregulatory cooling. They don't sweat as much to cool themselves down. And what's also been interesting is that there's other work that shows that when people with depression get better, when their depression symptoms lessen, their core body temperature also can decrease. And that's in the context of other treatments that aren't related to sauna treatment, for example, electroconvulsive therapy, ECT. There was a paper that showed that with successful ECT treatment, the patient's temperatures dropped alongside their depression. And from that Hanusch paper, that single-arm sauna trial, what they found was that the decrease in body temperature was correlated with a decrease in depression. And they measured that decrease in body temperature pretty carefully. They were using an indwelling rectal probe. So they were really measuring it those five days afterward, and that says something about the mechanism here with body temperature.

Dr. Patrick: And thermoregulation, perhaps, somehow, sauna use changing the thermoregulatory...

Dr. Mason: Turning it on, possibly.

Dr. Patrick: ...system somehow.

Dr. Mason: Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Patrick: Now, this is a...when you were talking about, you know, clinically depressed people, you know, most people experience depressive symptoms in their lives because of events that happen, maybe a death of a loved one, or stress from work, or financial stress, or relationship stress. I mean, there's a lot of life experiences that can cause, you know, like, people to be sad. But you're talking about something different here, right? You're talking about a clinical type of depression, which isn't just, you know, feeling sad, you know, or anxious because of a certain experience. You're talking about...

Dr. Mason: Right. Being depressed or down most of the day, nearly every day, for quite a few days. This is major depressive disorder, so it's an actual mental health disorder.

Dr. Patrick: Right. And those people, like you were saying, there's a correlation between not regulating the body temperature, correctly and that type of [crosstalk 00:13:26.549].

Dr. Mason: In some studies, there are...some samples...and, again, these are small samples, but what the researchers have found is that these patients' body temperatures are higher and that when their depression symptoms improve, the body temperatures decrease. So there's something there. And also that these people's body temperatures just tend to run hotter than other non-depressed samples.

Dr. Patrick: Do you know if...this is off-topic, but do you know if stress itself or stress hormones, or, you know, something there changes the thermoregulatory system? So, for example, if someone were to have, like, some sort of serious stress, like death of a loved one or something, and the stress, do you think that could possibly cause dysregulation of that system? Is there...?

Dr. Mason: I can't speak...

Dr. Patrick: Is that off the wall question, kind of?

Dr. Mason: I can't speak to the data, because I don't know the data on that. But it seems plausible that if we become really distressed and start to experience some of the symptoms that people with major depressive disorder are experiencing, and we're experiencing them, and it's somewhat of a prolonged way, that we could develop that. But we just don't have the data right now. There's a lot of depression that is situational, as you described, a lot. But there's also depression that's biological. And so we don't know so much which camp that's falling into.

Dr. Patrick: Right. I think another plausible mechanism...I know Chuck and I, or Dr. Charles Raison and I discussed this, and you and I as well in conversations that we've had. But inflammation...and this, I know, like, there are studies that have shown you can take a healthy individual who is not known to have any sort of clinical depression, and you can inject them with lipopolysaccharide, which is, you know, a piece of the outer membrane of bacteria, and it causes a very potent inflammatory response in humans. You inject them with the lipopolysaccharide, and they have an inflammatory response. They have activation of their immune system. The body's like, "Oh, bacteria. I got to fight it off. I don't want to get sick." So inflammation is generated. And, as you know, and we've talked about a lot in the podcast, you know, inflammatory molecules cross over the blood-brain barrier, and they disrupt neurotransmission in there, all sorts of things happening, you know, microglial activation. And what's been shown is that people experience...healthy people experience depressive symptoms after being injected with this lipopolysaccharide, versus a saline control. So people, individuals that were injected with saltwater, didn't have those depressive symptoms when they did some sort of questionnaire or scale, which you're familiar with, probably, but not me. But what was interesting is that, in addition to that, people were given a high dose of EPA, which is one of the marine omega-3 fatty acids that's very potent at negating inflammation. And the people that were given that and injected with lipopolysaccharide didn't experience the depressive symptoms. What I'm getting at here is that, you know, it seems as though that study itself...and there's actually is more than one that showed this. You could cause or induce depressive symptoms in healthy individuals just by causing inflammation. And you could prevent that by giving someone "something that's anti-inflammatory." Which I thought was so impressive and amazing and important because, you know, inflammation, there's so many sources of inflammation. So many different lifestyle factors, obviously, you know, sickness. I mean, people do feel depressed when they're sick, too. But the sauna and inflammation and how the sauna affects inflammation is a whole other interesting area, and particularly because, you know, we know for a fact that...lifestyle factors that can improve depression. And, you know, your specialty is non-pharmacological treatments. You know, of course, exercise is one of the big ones, right? I mean, exercise has been shown in multiple studies to help improve depressive symptoms in people with, you know, major depressive disorder or have clinical depression. And, of course, it's not easy to get someone who's depressed to exercise. But the fact of the matter is that it does work, in some cases, not all the time, but it does work. And the sauna, and there's many different ways that the sauna does mimic cardiovascular...moderate cardiovascular exercise. We have a lot of the same physiological responses, the increase in blood flow to the skin, the sweating to cool down the core body temperature, which increases with aerobic exercise. It also increases with sauna. Elevated heart rate, you know, blood pressure changes, the blood pressure increases while you're exercising or while you're in the sauna, then afterwards, it goes down even below baseline level, so lots of different similarities. And, of course, there's been head-to-head comparisons comparing moderate aerobic exercise to sauna use. So there's definitely some overlap there. So, you know, what are your thoughts on, like, well, maybe this is also helping depression in a similar way that exercise or specifically cardiovascular exercise would?

Dr. Mason: Yeah, absolutely. I think the pathway is totally plausible. But you hit the nail on the head. A lot of times, we would love it if we could get people with depression to exercise. But that is just too much to ask, in a lot of cases. It's also the case that not everybody can necessarily just go and exercise. I know that sounds a little bit crazy, but there are actually lots of people who have injuries or other problems that prevent them from engaging in the kind of exercise they would need to do to have that antidepressant effect, which is aerobic exercise, right? I think running is one of the most well-looked at ones, and it works well for mild and moderate depression. Remember, a bunch of these studies have divided out the depression by mild, moderate, and severe to look at which ones exercise works for best. And I don't quite recall off the top of my head at this moment which it was the best for. But getting people with mild depression to exercise, I think, is much more feasible than getting people with severe depression to exercise. But if we're able to actually capitalize on sauna, if people are more open to using whole-body heating practices, then maybe we have an avenue in to get at some of those biological pathways that exercise is triggering, like you just described. And that's why I think it's really important to start measuring those pathways in whole-body hyperthermia studies. And I'm not aware of any whole-body hyperthermia study looking at depression as an outcome that has measured those. So that's on our to-do list.

Dr. Patrick: Right. Yeah. I mean, that's something... So you've got a couple of studies one that's probably like...it was like a proof-of-principle-that-it's-safe study.

Dr. Mason: Yeah, yeah. It's under review right now. We did a study...right before COVID struck, we finished up this 25-person study to develop the protocol that we're going to be using at UCSF for our future trials.

Dr. Patrick: Maybe you can talk about why. So you talked about this Heckel machine, and it's very expensive, and it's, you know, made in Germany, but that's not what you're using.

Dr. Mason: No.

Dr. Patrick: So maybe we can talk about what you're using and why and your personal story about how you came to figure that out, because it's pretty funny.

Dr. Mason: It's a pretty funny one. So after that paper in 2016 came out and I got all excited about the study, and I emailed Chuck, or Dr. Charles Raison, about it and started talking about, how could we do this research? Well, it turned out it was actually really difficult to do research with that machine without a lot of money and without a lot of resources. And at the time, I was pretty junior at UCSF. I had just become an assistant professor, just gotten my first big NIH grant and wanted to figure out, well, how can we do this? And not only can how can we do this in a way that's feasible in science, but how can we actually develop something that could be taken out of the hospital that is actually more accessible, that might even someday be able to be in all kinds of settings, not just hospitals, maybe something that could be transitioned into someone's home? And how can we make this more affordable? There's enough health care that's unaffordable, let's not add to that list. So I decided to see what I could do, and gathered a group of friends and said, "Hey, guys, we need to go and figure out if we can find a sauna that can get our core body temperature up as hot as this machine can." So I went to Walgreens and bought a whole bunch of thermometers, handed them out and said, "All right guys, here's the list of all the different places to go and try these different saunas." And there was a Russian banya, there were a bunch of health spas, there were some other spas that have started having these infrared saunas. I have some friends who had infrared saunas in their house by that time. And everybody just started doing a bunch of testing for me. And we learned really quickly that man can't get to that core body temperature, because you can't stand to stay in that long. In these protocols, the Janssen protocol and the Hanusch protocol, people were in the sauna for well over an hour...two hours, in the Hanusch case, and I think 107 minutes on average in the Janssen paper. That's a long time to be in that little device.

Dr. Patrick: You'll never be in a 179-degree-Fahrenheit sauna for that long.

Dr. Mason: No.

Dr. Patrick: Absolutely impossible.

Dr. Mason: Absolutely not.

Dr. Patrick: You shouldn't it would be detrimental to your health.

Dr. Mason: Very dangerous, bad idea.

Dr. Patrick: So you were going around sticking thermometers in your butt...rectal, right?

Dr. Mason: Definitely, that's what everybody was doing.

Dr. Patrick: So that's the most accurate way to measure core body temperature.

Dr. Mason: Best way.

Dr. Patrick: And what increase in core body temperature? Was it a two, or two and a half? What was the degree?

Dr. Mason: Yeah, looking for about...on average, if people run their baseline between 97 and 99, right, a 2-degree temperature change could mean a lot of things for different people. So I was really looking to see, could people get to 101.3, because that was the temperature in the Janssen and Hanusch protocols. And it turns out the overwhelming answer was, well, no.

Dr. Patrick: What about the 20 minutes at 190? Where does that get you, 190 Fahrenheit?

Dr. Mason: I don't know. There was only...

Dr. Patrick: That's my typical sauna.

Dr. Mason: There was only one place, I think, that we could find that had a sauna that hot, and that was a Russian banya in San Francisco. All the infrared ones don't get that hot, actually. And so...

Dr. Patrick: Yeah, no infrared definitely was like 140?

Dr. Mason: They don't. One forty to 160 I think...

Dr. Patrick: One sixty, okay.

Dr. Mason: ...you can get up there. There's a bunch of variability, though. So, anyway, ultimately, I only ever had a couple of friends who were able to get that hot maybe once or twice. And they said it was relatively excruciating. They thought they were going to faint. Like, you know, the descriptions that they gave me would never have passed through the Institutional Review Board at UCSF. And I thought, "What am I missing here? What's the key detail?" But it turns out that key detail is having your head out of the sauna. So then we rebooted and started looking around for heating devices where your head is not inside of it. And, behold, found one of these sauna domes. And got a few of those, started testing that out. And it turns out, you can stand to be in that thing for a lot longer than to be in...

Dr. Patrick: So this is an infrared sauna dome, head out.

Dr. Mason: Head out.

Dr. Patrick: And it's like something you can just buy on Amazon or something.

Dr. Mason: You can buy one on the internet. There are so many kinds. Now, obviously, we had to pick a kind and then had to do...we had to apply for something called a nonsignificant risk determination through the UCSF IRB in order to be able to use it. I had to write up a whole protocol, say what I was going to do, say how it was going to work, how I was going to keep people safe, all of these things. They had to review it. It took about a year to get the approvals to do that one first study. And you might be wondering, "Well, okay, so people are lying in this tube..." Doctor Raison sent me his Mindray rectal probe machine that I could use for the study, which is a rectal probe that's in there the whole time. It's silicone. It's not a big deal. And no one in the study that I did with 25 people had any complaints or anything about it. As soon as they saw it, they said, "Oh, that's not a thing. I can put that there." And it was no big deal. And in order to keep people able to stand this for that long, we developed a whole protocol where a person sits at the head of the person who's in the sauna and is giving them water when they're thirsty. And, most importantly, is using giant ice cubes and cold cloths all over their head to keep them cool in their head. And it's remarkable what a difference this makes and what a role it plays. And it helps people stay calm, it helps them stay comfortable. Because we did some test runs with folks with and, you know, without it as much, and people were overwhelmingly more comfortable when they had ice on their face. Turns out, you do this protocol, people can stay in the sauna. It takes about 70 to 80 minutes. It was comparable to the protocols from the Janssen and Hanusch papers. And we were off to the races. So we did it with 25 people, and those data are under review now.

Dr. Patrick: What temperature was it, the dome?

Dr. Mason: It was about...gosh, it's hard to say. I think it was about between 144 and 150-ish. It was not as hot as you would think.

Dr. Patrick: And it was on the entire 80 minutes?

Dr. Mason: And so that's another really important thing. So I think there's a whole category of things we've discovered from the existing literature. And one of the really important ones is that the time that you are taking to get to that temperature also might really matter. When people got into those sauna tents in those two other studies, they were cold. And then the researchers turned them on and heated them up. And so that's what we did in our study as well. They got in, we turned it on, and then they heated up as the ambient air heated up. And in a recent paper that, actually, incidentally, Janssen and Hanusch had written together, they reviewed some of the studies that exist for looking at whole-body hyperthermia for depression. And one of the things they noted is that the effect sizes of the change in depression from before to after the intervention, in other words, the size of the reduction in depression, was higher if people spent more time getting to that peak temperature. So longer seemed to be better. And, in hindsight, that's not really rocket science. I mean, it makes a lot of sense. If you take a frog and you throw it into boiling water, it jumps right out, because it says, "This is too hot, I can't stand this." But if you put the frog in the cold water, and then you slowly heat it up, it can stand to be in the heat for a whole lot longer. And it's going to get much more of the effects than the brief amount of time it was in the boiling water. So this paradigm where we start people cool might have multiple effects. One, it might help people actually be able to endure this treatment better. Because if you and I are thinking...oh, getting into our 190-degree Finnish sauna, like, it's hot, the minute you get in you are going. But these people don't start with that shock. They're just like, "Okay, I'm lying here. It's getting warm. It's getting warmer." And maybe it helps them withstand it and be able to do it longer. Because, as I said, it's not a spa treatment. It's not a walk in the park. It's intense. And so, I don't know exactly where we started with that, but I got all excited about how this protocol is working.

Dr. Patrick: What's interesting, though, also, because you mentioned, like, for example, I get into this 190-degree, you know, Fahrenheit degree sauna, and I want that thing hot when I get in. I don't want to waste my time, you know. [inaudible 00:29:18] be hot. I'm going to get in there. I'm going to sweat. But I'm also heat adapted. And, you know, there have been studies showing that, you know, the more you expose yourself to heat, whether...or the more you elevate your core body temperature, which can be through, you know, ambient heat, so like a sauna, or a hot bath, or a steam shower or...

Dr. Mason: Exercise.

Dr. Patrick: ...yoga or exercise, the more adapted you become. So your body starts to sweat at a lower core body temperature to cool yourself down. All these other physiological changes start to happen. Your heart rate variability, you know, improves. All those things happen when you're adapted. And when you're adapted, it becomes easier. It's like, "Oh, I'm sweating at a lower core body temperature, so I'm feeling cooler, and I can stay in easier," right? And also heat shock proteins. We'll talk about biomarkers for heat shock proteins, which are proteins that are, you know, classically known to be involved with...you know, they're stress response proteins. So heat is a form of stress, and they get activated with many types of stress, but heat is one of them. And they basically protect proteins inside of your cells from aggregating and becoming misfolded and forming plaques and disrupting things. They also help prevent muscle atrophy. They play a role in preventing your muscles from atrophying. And they play a lot of neuroprotective roles and neurodegenerative...they do a lot of things. But they also kind of help your body deal with the heat stress, and this is part of the adaptation. And so people with, like, higher levels of heat shock proteins, so people that are heat adapted, they increase their heat shock proteins upon exposure to heat sooner than people that are not adapted. And so, kind of, what you're saying makes sense where you're not just shocking them all at once, but they might be slowly adapting in a way, you know, like, on a physiological level.

Dr. Mason: It could be, and it's their first time, so it's very new. They're not adapted in any way to that yet.

Dr. Patrick: Totally. I've noticed, like, with, for example, my mom, who...boy, she can sweat at, like, the minutest little temperature change where she's like, "It's hot here. Where's my fan?" you know? So I've been getting her in our sauna, and the first time she got in, it was like five minutes. And I did it at 165, which is typically what a lot of gyms are at, 165 Fahrenheit. She was like, "I couldn't..." She couldn't stand it for more than five minutes. And I said, "That's okay. It's your first time, you know." And then the second time she did it, she was in there less than 10, but it was more than 5, you know. And then now she's like, you know...I mean, she can stay in there 10. But sometimes what she'll do is she'll stay in there for 10 and then get out. She'll get on the lower bench. She'll get out for a couple of minutes and then come back in. But the first couple of times, it was like, "I can't do this. This is too much," you know, "for me."

Dr. Mason: That's why it's so important to develop these protocols in ways that people will actually do them. Because as much as we wish, you know, we could have people do all kinds of things, exercise or eat certain things. If people won't do it, then it won't work.

Dr. Patrick: Right. Yeah. And you mentioned this also, which is a very important point, is there are a lot of disabled people. Like, there are people that can't go for a run, whether it's joint injuries or something more severe. I mean, there are people that can't do, like, aerobic exercise. And there are also people that have never done it in their entire life, and they're older. And it's like, good luck getting someone who's never been physically active to, like, start being physically active in their six-decade of life. It's really hard. So the sauna, it's not only, like, you know, more applicable in the sense that people are more compliant, because it's easier to go sit in something than it is to go for a run. But, I mean, people that can't go for a run, like, physically, that's amazing, right? I mean, being able to do that.

Dr. Mason: And I think that's where this comes in, too, for thinking about cardiovascular disease, which I know you've thought a ton about, and you gave that talk about, and, you know, it's a big theme. And one of the things we should definitely mention is that cardiovascular disease and depression, those often happen together. And so there's a large group of people who are struggling with cardiovascular problems, and also depression, for whom this may be a treatment that could have an effect for both conditions. So one of the other aspects to think about when developing a protocol like this is, can we use it for other conditions too not just mental health, but maybe also other physical health conditions that are affected by exercise and heat?

Dr. Patrick: Right. So let's talk about the...so you're now doing a study.

Dr. Mason: Yes.

Dr. Patrick: Hopefully, you're starting soon. COVID's delayed it a bit. It's delayed much research in the world. But let's not talk about that. So this new study that I'm super excited about, and I get to play a very small role, collaborative role with you.

Dr. Mason: It's going to be so fun.

Dr. Patrick: Let's talk about it. Because biomarkers, which is where I come in with my enthusiasm...

Dr. Mason: Absolutely.

Dr. Patrick: ...and being able to look at, you know, how a sauna may affect people with depression at, you know, like a real molecular level, right?

Dr. Mason: Yeah, in the cells.

Dr. Patrick: Yeah. So let's talk about that study, which hopefully will start very soon.

Dr. Mason: So we're really looking forward to this study. It's going to be a three-year project to do this pair of two studies. The first study will be 16 people, and everybody's going to get the same thing. And I'll talk about what that is in a second. And the second study is going to be 30 people. And half of those people get one thing, and half of those people get another thing. So let's talk about what everybody is getting in the first study. So, first of all, in both these studies, we're going to measure all of those biomarkers. It's going to be pretty exciting. You've mentioned a number of them so far, BDNF, heat shock proteins, inflammatory cytokines, gosh, CRP. There's a little bit of a laundry list we've got going.

Dr. Patrick: So people that don't know what BDNF is, brain-derived neurotrophic factor. And what role does that play in depression, just, like, generally speaking?

Dr. Mason: My goodness. So I'm not up to snuff, I would say, on all of the biological underpinnings with these molecules with depression. But there's...

Dr. Patrick: It's one of the things where exercise has been shown to increase, and it's thought that may help with neuroplasticity.

Dr. Mason: Right. But there's been a whole bunch dating back to Dr. Charles Raison's paper in 2007, called "Cytokines Sing the Blues," looking at how depression may be quite inflammatory for some people who have it. And so we know that exercise is temporarily inflammatory when you do it, but it's actually in a good way because of the adaptive changes that follow from that.

Dr. Patrick: The anti-inflammatory change.

Dr. Mason: Yes, right. So the thought is, well, sauna is hopefully quite similar. And we have a bunch of data that suggests that it is looking in that direction. We still need to do the research, though. So in this first study, we will have 16 people with major depressive disorder. We will recruit them. They will all be adults. And in addition to getting a whole-body hyperthermia treatment, they're also going to get something called cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. So what is that? Cognitive behavioral therapy is a psychotherapy used for depression. It's considered gold standard. It's a first-line treatment for depression. It doesn't involve medications. It's just a therapist who provides this treatment. It's pretty structured. It's pretty standardized. There are very specific tools that are often used across all of the different ways of administering this treatment. But the idea is that thoughts impact our feelings, and how we feel impacts our behavior. So, for example, if you have someone who has, let's say, type II diabetes, and they come in and they say, "I'm never going to be able to get my blood sugar under control. I'm never going to be able to do it. I just can't seem to stick to this diet. I'm always going to fail. I'm never going to be able to do this." When someone has those series of thoughts, how do you think they feel? Not so great. They don't feel so great. And when you don't feel so great what do you do? Well, the chocolate cake sounds pretty good. Maybe I'll eat some chocolate cake to feel better. But then you eat the chocolate cake, which reinforces the thought, "I can't do this. I'm never going to be able to stick to this diet," and so on and so forth. So thoughts, feelings, behavior, thoughts, feelings, behavior. And so interrupting that loop is a major part of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, and there's a bunch of different ways that that's done. Anyway, this treatment is known to work. However, it doesn't work if people won't do it. And what is one of the major reasons why people with depression can't really get some benefits out of psychotherapy? They can't really engage, because they're super depressed. Notwithstanding, of course, there are huge problems with our medical health care system in terms of being able to get therapy. That's a whole nother can of worms that we don't need to go into. But the point that I'm making is just that if patients can't really engage in therapy, they can't really get the benefits out of therapy. So, in this treatment, everybody's going to get whole-body hyperthermia, as well as cognitive behavioral therapy sessions. Not at the same time. They might be on separate days, or they might be on the same day, but one after the other. And you might be wondering, well, where did this idea come from? Like, why give cognitive behavioral therapy with whole-body hyperthermia? And that dates back to a few different things. And I think you and Dr. Charles Raison talked about this during your discussion about some of the traditional origins of sauna. It's often been a communal process, Native American sweat lodges. People don't go on those by themselves, right? It's a group. Or in the Korean kilns, or in the Russian banyas, right? It's been a social experience. And one thing that Chuck told me about the 2016 paper and about that study was that, during the study, the patients who were getting the whole body hyperthermia often started chatting. I don't remember if you guys talked about this part or not, but...

Dr. Patrick: Just from personal experience, it's absolutely true. I mean, you become chatty when you're in the sauna. And, like, you talk to people when...yeah.

Dr. Mason: Yeah, started wanting to connect, started wanting to...and so the research assistants went back to the investigators and said, "The patients are talking. What should we be saying to them? What should we be doing?" And I remember when Chuck told me this story and just thinking, "Well, if whole-body hyperthermia is making people want to talk more, and one of the major reasons why people don't do well in therapy is that they don't want to talk, and they don't want to engage, should we be pairing these things? Could using heat then cause people to be able to be more engaged in therapy?" And so this is the ultimate mind-body type intervention, right? There's no drugs here. And if we can develop something like this, that gets around prescribing people medications, maybe this is a good way to go. So proposed this dual intervention with a mind and a body component, and that's what we're moving forward with. So we're developing that combined intervention. And then in the second study, with the 30 people, we're randomizing half of people to just get the cognitive behavioral therapy, which we know works. It's in the literature. There's reviews, meta-analyses showing that cognitive behavioral therapy for depression works. Half people will get that and then half will also get the whole body hyperthermia sessions. And we will see, does adding the whole-body hyperthermia lead to larger depression decreases? And you might be wondering, "Well, why don't you do it differently? Why didn't you just do just the sauna versus, like, just CBT or something like this?" Well, it's really tricky ethically to recruit patients with depression and then not provide them with a treatment that we know works. And tell them, "Oh, and by the way, don't do anything else while you're doing this thing." That's a very, very tricky thing to do. The better thing to do is to say, "Okay, here's what we know we have already. Can we do better than that?" One of the key gaps that we're addressing is we're going to be giving people eight weekly whole-body hyperthermia sessions.

Dr. Patrick: Right.

Dr. Mason: So that's a lot. We're going to see, are people willing to do this? Do they get more benefit this way? Because those other two studies that I mentioned, they only gave one whole-body hyperthermia session, and we saw that huge drop one week later. What happens if we give a second session one week later? Are we going to see another huge drop? We don't know. We need those data. So we're going to be doing multiple whole-body hyperthermia sessions. We're also going to be measuring body temperature at night, during their entire time that they're in treatment, because they're going to use a wearable device to do that.

Dr. Patrick: When they're sleeping.

Dr. Mason: When they're sleeping instead of using, you know, an indwelling rectal probe. But that's kind of a hard sell to get people to wear that for, like, I don't know, 10 weeks. I don't think they're going to go for it. We're going to measure depression symptoms daily using smartphones so that we can actually see when symptoms are changing. We're going to measure all those biomarkers, and we're going to have all these in relation to each other. And one of the things I really hope we discover, too, is, how willing are people to do this kind of sauna treatment? And then, you know, obviously, seeing how long it lasts. We're going to measure outcomes further than one week and six weeks, obviously. But what my hope is, is that we might be able to develop almost a booster method if, in the future, this seems like a good idea after this next study. And I really hope it does. But you see on the internet that you can buy all these sauna tents that you can use at home. You know, with people...there's always a picture.

Dr. Patrick: Oh, people have them, yeah.

Dr. Mason: And they've got their hands out, and they're reading their magazine, and their head is out, and it looks kind of funny. You could see them on all the different websites. Well, what if we actually need to do a certain number of this intensity of whole-body heating, like the kind that we're talking about here? But then at home, it can be supplemented, and it could be maintained or sustained in this way. And that's a great model moving forward. Would people rather, you know, take drugs that maybe aren't working so well, or maybe come with a certain number of side effects, or say, "Oh, once a week, I have to sit in this thing for 45 minutes and read a magazine," right? So if we can develop a longer-term model for maintaining wellness and maintaining reductions in depression symptoms, that would be a huge win.

Attend Monthly Q&As with Rhonda

Support our work

The FoundMyFitness Q&A happens monthly for premium members. Attend live or listen in our exclusive member-only podcast The Aliquot.

Sauna News

- Hot water immersion more than doubles core body temperature rise compared to traditional saunas, potentially boosting vasodilation, cardiac output, and immune activity.

- Regular infrared sauna use increases blood vessel density in aged muscles by 33%, though muscle size, strength, and protein synthesis remain unchanged.

- Post-exercise hot tubs and saunas show minimal, inconsistent benefits in exercise performance enhancement, despite potential physiological effects.

- Post-exercise infrared sauna use contributes to a 25% increase in jump height and a 6.8% peak power boost in female athletes—a potential tool for enhancing power production.

- More than 3,600 food-contact chemicals used in packaging and storage detected in humans, including several toxic substances associated with cancer, fertility issues, and hormone disruption.