Berberine Suggest an improvement to this article

Contents

[HIDE]- Background

- Anti-diabetic and glucoregulatory effects

- Weight gain and metabolic syndrome

- Cholesterol-reducing effects of berberine

- Hypertension and congestive heart failure

- Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer benefits in the gut and liver

- Brain and neurological disease

- Anti-aging effects

- Mechanisms of action

- Berberine versus metformin

- Berberine pharmacokinetics

- Toxicity profile and drug-drug interactions

- Conclusion

- Related resources

Background

Berberine is an alkaloid compound present in the roots, stems, rhizomes, and bark of a variety of plants, including Californian poppy, goldenseal, cork tree, Chinese goldthread, Oregon grape, and several plants in the Berberis genus. It is also widely available as a dietary supplement. Berberine has a long history of use in the ancient and traditional medicine systems of India, China, and Persia. Research demonstrates that berberine may exert pharmacological effects against certain chronic health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, neurodegenerative disease, depression, and metabolic dysfunction. Some of berberine's effects mirror those associated with metformin, an antihyperglycemic agent commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes. Preliminary research in animals also suggests that berberine may exert anti-aging properties and might be beneficial in combating aging-related diseases. However, the bulk of research involving berberine has been conducted in animals, with a paucity of trials in humans. This article provides an overview of the evidence demonstrating the beneficial health effects of berberine and compares and contrasts the compound's effects and mechanisms of action to those of metformin.

Anti-diabetic and glucoregulatory effects

"[Clinical] trials demonstrated that berberine was generally as effective as conventional antihyperglycemic agents, especially when participants engaged in lifestyle modifications to mitigate their diabetes." Click To Tweet

Oxidative stress and inflammation play critical roles in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance, diabetes, and their associated complications. Berberine has long been used as an effective treatment for diabetes in traditional Chinese medicine, likely due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.[1]

Evidence from rodent studies suggests that berberine enhances pancreatic islet cell function, reduces LDL cholesterol, and ameliorates the harmful effects of diabetes on the kidneys.[2] [3] The results of human studies of berberine's effectiveness against diabetes have been mixed, however.

A randomized clinical trial involving 97 people with diabetes compared the effects of berberine, metformin, and rosiglitazone for two months. Berberine (1 gram per day) lowered the participants' fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin (Hb)A1c (a measure of long-term blood glucose control), triglycerides, and insulin levels. The effects of berberine on blood glucose levels (26 percent reduction) and HbA1c (18 percent reduction) were comparable to those achieved with metformin and rosiglitazone.[4]

A meta-analysis of 14 clinical trials involving more than 1,000 people with diabetes found that the trials differed markedly in terms of design, dose, and duration.[1] Some of the trials employed multiple strategies to mitigate diabetes in conjunction with berberine, including lifestyle modifications, antihyperglycemic agents (such as metformin, glipizide, or rosiglitazone), and aspirin. Berberine doses ranged from 0.5 to 1.5 grams daily, provided in two or three doses. Trial duration ranged from eight to 24 weeks. The trials demonstrated that berberine was generally as effective as conventional antihyperglycemic agents, especially when participants engaged in lifestyle modifications to mitigate their diabetes. Berberine potentiated the effects of antihyperglycemic agents when used in conjunction with the drugs. Few adverse effects were noted other than mild gastrointestinal discomfort. The authors of the analysis conceded that the trials reviewed in the analysis were of poor quality and advocated for better-designed trials in the future.[1]

A more recent meta-analysis of studies involving 2,500 participants with diabetes provides even stronger evidence of berberines' metabolic benefits. Researchers found that berberine supplementation with lifestyle modifications reduced HbA1c, normalized blood lipids (i.e., cholesterol, triglycerides), and lowered blood pressure better than lifestyle modifications alone and better than placebo supplementation.[5]

Weight gain and metabolic syndrome

Excess body weight contributes to a wide range of health disorders, including metabolic syndrome. Findings from a randomized controlled trial demonstrate the efficacy of berberine supplementation in preventing weight gain and metabolic syndrome among patients taking antipsychotic medications, which cause predictable weight gain, glucose dysfunction, and dyslipidemia, contributing to higher rates of cardiovascular disease in people with severe neuropsychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The participants took a placebo or 600 or 900 milligrams of berberine per day for 12 weeks. Participants taking 600 milligrams of berberine per day had better cholesterol and glucose levels at the end of 12 weeks and lost 2.4 pounds more than the placebo group. Participants taking the higher dose (900 milligrams) exhibited similar improvements and saw these improvements faster after just eight weeks of supplementation.[6]

Cholesterol-reducing effects of berberine

Statins are typically the first drug of choice for improving lipid profiles, especially among people who are at risk for cardiovascular disease. However, as many as 10 to 20 percent of people taking the drugs experience complications, including myopathy (muscle damage) or liver damage. Statins lower blood cholesterol levels by blocking the production of an enzyme in the liver called hydroxy-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, commonly referred to as HMG-CoA reductase. Berberine also lowers blood cholesterol, but the mechanisms by which it elicits these effects (such as regulation of proteins involved in cholesterol metabolism) differ from those of statins. Interestingly, berberine use in conjunction with statin therapy has been more effective than either compound alone.[7]

Animal evidence

Multiple studies in rabbits and rats fed obesity-promoting diets demonstrate that berberine reduces serum total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides and increases high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Evidence suggests berberine also modulates factors involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.[8]

Human evidence

Human studies demonstrate similar effects. A clinical study assessed the effects of 500 milligrams of berberine versus a placebo taken twice daily for three months in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 144 people. The participants who took the berberine lost weight and saw improvements in their total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol compared to the placebo group.[9] A separate study involving 228 people who had high cholesterol but were unable or unwilling to take statins investigated the effects of berberine, ezetimibe (a cholesterol-lowering drug), or the two compounds together in modulating cholesterol levels. The findings indicated that a nutraceutical product containing berberine, policosanols, and red yeast rice reduced LDL cholesterol by nearly 32 percent, while ezetimibe reduced it by approximately 25 percent. In addition, berberine elicited fewer side effects.[10]

A larger clinical trial with more than 1,380 participants who did not have diabetes found that taking a proprietary supplement that included berberine for eight weeks increased HDL cholesterol and reduced non-HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, waist circumference, and blood pressure, all biomarkers used to diagnose metabolic syndrome. Overall, participants who met the criteria for metabolic syndrome at the end of the trial significantly decreased.[11]

"Participants who took berberine lost weight and saw improvements in their total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol, compared to the placebo group." Click To Tweet

Hypertension and congestive heart failure

Berberine exhibits pharmacological action in a variety of chronic diseases.

Hypertension damages blood vessels and promotes kidney failure. In a rodent model of hypertension, berberine administration delayed the onset and reduced the severity of hypertension by reducing angiotensin II and aldosterone (hormones that elevate blood pressure). The compound also reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-17, and IL-23, which drive blood vessel and kidney damage.[12] Similarly, berberine promoted aortic relaxation in isolated mice aortas, induced relaxation of mice vascular smooth muscle cells in culture, and lowered systemic blood pressure in hypertensive mice. These effects were attributed to the suppression of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel – a protein that plays roles in vascular function, among others.[13]

Congestive heart failure is typically described as the end stage of heart disease. The potential role for berberine in treating congestive heart failure was observed in a rat model, when high doses of the compound improved several markers of cardiac function, including left ventricular end-diastolic pressure – the amount of blood in the heart's left ventricle and a measure of the risk of subsequent heart failure.[14]

Clinical trials are needed to fully elucidate the cardiovascular benefits of berberine in humans.

Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer benefits in the gut and liver

"In a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial involving people with IBS, berberine reduced diarrhea frequency, abdominal pain, and the urgent need for defecation." Click To Tweet

Berberine may have beneficial effects in multiple tissues in the gut, especially the liver and intestine. However, much of the data demonstrating these effects come from cell culture studies and may or may not have applicability to humans.

In the liver, cell culture studies demonstrate that the compound inhibits the proliferation and growth of hepatic stellate cells, the primary driver in the development of liver fibrosis.[15] A rodent study in which rats received berberine at 50, 100, or 200 milligrams per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg/bw) per day demonstrated that tissue changes such as steatosis, necrosis, and myofibroblast proliferation, as well as several markers of liver dysfunction, decreased when compared to controls.[16]

Other cell culture studies demonstrate that berberine may provide protection against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, a syndrome that encompasses multiple states of liver dysfunction, including steatosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and cirrhosis. Multiple mechanisms associated with this protective effect have been identified and center on aspects of improved glucose and lipid metabolism, reversed methylation states of genes that participate in lipid metabolism, and enhanced antioxidant capacity of liver cells.[17] [18] [19] [20]

Clinical research needs to confirm whether berberine has beneficial effects on the liver in humans.

In the intestine, berberine appears to be beneficial in reducing factors that drive inflammatory conditions. In cell culture studies, berberine reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and apoptosis in the gut – two hallmarks of inflammatory bowel disease.[21] The compound also improved symptoms associated with irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, in humans. In a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 132 people with IBS who took 400 milligrams of berberine or a placebo twice daily for eight weeks, participants experienced reduced diarrhea frequency, abdominal pain, and the urgent need for defecation. Interestingly, the participants also reported improvements in quality of life and reduced levels of depression, a common feature among people with IBS.[22]

Additional clinical research is needed to confirm whether berberine has beneficial effects on the intestine in humans.

Brain and neurological disease

Berberine acts on multiple pathways and processes that promote neuroprotection and overall central nervous system health.

Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease

Berberine elicits variable effects on the pathogenic processes involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease. For example, daily oral administration of berberine at 20, 50, or 80 milligrams per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg/bw) prevented damage to dopaminergic neurons and improved short-term memory in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease.[23] Similarly, in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease, oral berberine (40 mg/kg/bw) per day increased autophagy, which, in turn, promoted cellular degradation of mutant huntingtin, the protein implicated in the pathogenesis of the disease.[24] A mouse study that investigated the effects of berberine on neuropathic pain associated with diabetes demonstrated that berberine suppressed microglia and astrocyte activation and inhibited expression of proinflammatory cytokines that drive neuropathic pain.[25]

Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons

Berberine promoted the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in cell cultures and in a rat model of Parkinson's disease and reduced dopamine levels in the substantia nigra, the region of the brain most affected by the disease.[26] [27] The authors of an extensive review of the effects of berberine on the neurological system found that berberine generally had favorable effects, but expressed concerns that dose- and species-dependent differences in berberine metabolism could alter some findings.[28]

Multiple sclerosis

Preclinical evidence suggests that berberine shows promise in treating the clinical symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis, or MS, a type of autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system. In a mouse model of the disease, oral berberine administration (30 mg/kg/bw per day) reduced several of the pathological hallmarks associated with MS, including blood-brain barrier permeability and factors that drive the degradation of myelin.[29] [29]

Depression

The antidepressant effects of berberine have been observed in mice. In particular, studies demonstrate that berberine administration modulates levels of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine – neurotransmitters that influence mood – by increasing their uptake in the brain.[30] [31] A mouse study demonstrated that oral berberine (50 or 100 mg/kg/bw per day) reversed the depression-inducing effects of corticosterone injection by upregulating hippocampal synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor – a type of protein that acts on neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems and may be important for the antidepressant response.[32] [33]

Clinical trials are needed to fully elucidate the neurological benefits of berberine in humans.

Bodyweight distribution and metabolism in polycystic ovarian syndrome

Polycystic ovarian syndrome, or PCOS, is a hormonal disorder characterized by menstrual irregularities, metabolic dysfunction, excess hair growth, acne, and obesity. The condition affects as many as 10 percent of women of reproductive age.[34] Women with PCOS produce abnormal levels of androgens (male sex hormones) and often experience infertility.

Findings from an analysis of five studies involving more than 1,000 women found that berberine may be useful in managing PCOS. The studies revealed that women who took berberine experienced adipose tissue redistribution. In turn, the women's visceral fat mass decreased, even in the absence of weight loss. The women's insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles improved, too. Importantly, berberine improved insulin sensitivity in the women's theca cells, which are specialized endocrine cells in the ovaries that play roles in fertility. Consequently, the women's ovulation rate improved, with reciprocal improvements in live birth rates.[35]

It is noteworthy that the formulations used in the five studies varied considerably. Two studies administered 500 milligrams of berberine hydrochloride three times per day; one administered 588 milligrams of Berberis aristata extract twice daily; one gave 500 milligrams of berberine plus 3 milligrams of monacolins (a type of statin) once daily; and one provided 1.5 grams of berberine once daily.[35]

Anti-aging effects

Berberine exerts anti-aging effects in cell culture, insect, and rodent studies. Cell culture studies demonstrate that berberine attenuates cellular senescence, a process of deterioration that occurs with age.[36] Senescent cells can no longer replicate (divide) and are not metabolically active. They often release inflammatory cytokines, which can promote damage to neighboring healthy cells.

Berberine demonstrates anti-aging effects in skin cell culture studies due to its inhibitory action on the activity of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9, enzymes that play roles in ultraviolet light-induced skin damage and skin cancer.[37] Conversely, the compound promotes the activity of procollagen, a precursor to collagen and a critical player in skin integrity.[38]

Studies in insects demonstrate that berberine extends lifespan and healthspan. Fruit flies given berberine lived 27 percent longer and were 39 percent more physically active than a control group.[39] A different study found that berberine ameliorated the harmful, pro-aging effects of heat on fruit flies[40]

A multiple-model study of the effects of berberine on aging found that the compound improved several aspects of aging in human lung fibroblasts by promoting the cells' progression through the cell growth cycle. The cells' replicative capacity was longer, and their overall shape was more similar to younger cells. The lifespan of naturally-aged mice that were given berberine was nearly 17 percent longer and nearly 50 percent longer among chemotherapy-treated mice given berberine. In addition, the mice showed improvements in healthspan, fur density, and behavior.[41]

These data in cell culture, fruit flies, and rodents indicate that berberine may positively influence aging. However, whether berberine affects the aging process in humans is unclear.

Mechanisms of action

Multiple mechanisms of action have been proposed as drivers of the beneficial effects of berberine. These mechanisms capitalize on berberine's capacity to reduce oxidative stress via activation or inhibition of multiple cellular signaling pathways. Some of these pathways are described here.

The primary mechanism associated with berberine's effects centers on its activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, or AMPK, in multiple cell types, including endothelium, smooth muscle, cardiomyocytes, cancer cells, pancreatic beta cells, hepatocytes, macrophages, and adipocytes.[42] AMPK serves as a master regulator of cellular energy homeostasis by sensing cellular energy deficits. Its activation influences gene expression and inhibits cellular processes that drive oxidative stress.

Berberine also activates p38, an enzyme that participates in the body's stress response.[43] The co-activation of AMPK and p38 switches on the activity of Nrf2, a cellular protein that regulates the expression of antioxidant and stress response proteins. Nrf2 is an element of the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE biological pathway, which activates the transcription of cytoprotective proteins that protect against oxidative stress due to injury and inflammation.[44]

Berberine inhibits the activity of I-Kappa B kinase and Rho GTPase, enzymes that promote inflammation.[43] Inhibition of these two enzymes deactivates NF-kappa B, downregulating a cascade of pro-inflammatory events.

Biosynthesis of berberine. Source: Wikipedia

Berberine versus metformin

"Berberine and metformin differ markedly in their chemical structures and bioavailability, but they share many features in their activities against type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and inflammation." Click To Tweet

Some of berberine's effects mirror those associated with metformin, an antihyperglycemic agent commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes. Some evidence suggests that metformin may modulate the aging processes to improve healthspan and extend lifespan in multiple species, including flies, worms, and rodents, with limited evidence in humans. In addition, evidence suggests that metformin may prevent cognitive losses, improve mental health status, and reduce the risk of cancer. However, metformin may inhibit exercise-induced health benefits, especially regarding muscle mitochondrial adaptations and muscle hypertrophy.

The mechanisms by which metformin exerts its effects are not fully understood, but evidence suggests that metformin activates AMPK and inhibits mTOR, pathways involved in cellular energy and antioxidant responses.

Metformin and berberine differ markedly in their chemical structures and bioavailability, but they share many features in their activities against type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and inflammation.[45] Whereas evidence indicates that metformin blunts the beneficial effects of exercise, the evidence regarding berberine and exercise is somewhat mixed. Both compounds have low toxicity but are contraindicated in some (but differing) circumstances.

Effects on exercise adaptation: contrasting to metformin

Like berberine, metformin activates AMPK and other cellular pathways that reduce oxidative stress and damage. Evidence suggests that metformin inhibits mitochondrial adaptations and improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and diminishes whole-body insulin sensitivity after aerobic exercise.[46] Due to berberine's effects on AMPK activity and the subsequent reduction in reactive species, some researchers have posited that berberine may similarly blunt the effects of exercise.[47] However, an intervention study that investigated the effects of berberine and circuit training in sedentary, overweight men found that berberine enhanced the effects of exercise.[48] Similarly, berberine potentiated the effects of aerobic exercise in diabetic rats as evidenced by higher levels of antioxidant enzymes in the animals' pancreatic tissues.[49] Exercise to exhaustion can induce damage to the heart muscle, but berberine attenuates the harmful effects of exhaustion-induced heart damage in mice, likely via its inhibitory effects on the release of reactive oxygen species and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes.[50]

More clinical studies involving large groups of participants are needed to determine the effects of berberine on exercise-induced health benefits.

Berberine pharmacokinetics

Berberine undergoes extensive metabolism in the intestine due to active efflux of the compound via p-glycoproteins, a class of transporters involved in the clearance of xenobiotic substances, such as drugs, toxins, and polyphenols.[8] Consequently, oral berberine demonstrates notably poor bioavailability – as low as 1 percent or less – in rodent studies.[51] [52] However, the use of alternate delivery systems of berberine such as mucoadhesive microparticle formulation, anhydrous reverse micelle microemulsion, or oral microemulsion substantially increases the compound's bioavailability and subsequent plasma concentrations. [53] [54] [55]

Following absorption in the intestinal mucosa, berberine undergoes biotransformation in the liver via phase 1 and phase 2 metabolism to yield its primary metabolites, berberrubine, thalifendine, and jatrorrhizine.[56] The principal enzymes involved in phase 1 metabolism of berberine are the cytochrome P450, or CYP, enzymes, specifically CYP2D6.[8] Genetic polymorphisms that influence the expression of CYP2D6 subsequently influence berberine metabolism and should be taken into consideration when determining dose.

Interestingly, despite berberine's poor oral bioavailability and resultant low plasma concentration, it is found widely distributed in the body's tissues following ingestion, especially in the liver, kidneys, muscles, lungs, and brain. A rodent study reconciled this anomaly by demonstrating that gut microbes convert berberine to dihydroberberine, a more absorbable form of the compound (fivefold greater).[57] A study in humans indicated that berberine exhibited differential metabolism due to variations in gut microbial makeup related to dietary intake. One study demonstrated that plasma berberine concentrations were more than twofold higher among young African males than young Asian males, suggesting that personalized approaches to dosing berberine may be called for.[58]. The majority of berberine is excreted in feces, bile, and urine within 48 hours of administration.

Toxicity profile and drug-drug interactions

Berberine is well-tolerated and has low toxicity in rodents. However, the mode of delivery markedly influences the dose at which berberine is lethal. Whereas intragastric delivery is non-lethal, intravenous and intraperitoneal delivery can achieve lethal levels.[59] The most commonly reported negative effects of berberine in humans are diarrhea and constipation, observed with doses of 500 milligrams per day, especially when used in conjunction with anti-hyperglycemic agents. A dose of 300 milligrams given three times daily reduced the risk of gastrointestinal distress.[60] [61]

Berberine impairs the activity of enzymes that metabolize a variety of drugs, markedly increasing the bioavailability of ketoconazole (an antifungal drug), cyclosporine (an immunosuppressant), digoxin (an antiarrhythmic), and metformin.[62] [63] [64] The increased bioavailability of metformin when used with berberine raises particular concerns due to the compounds' capacity to decrease blood glucose levels. Caution is advised when taking the two together.

Conversely, findings from rodent and human trials suggest that berberine dampens the harmful effects of some pharmaceuticals, including cisplatin, isoniazid, bleomycin, doxorubicin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and others.[65] [66] [67] [68]

Conclusion

Berberine is a plant-based bioactive compound found in various plants and is widely available as a dietary supplement. Evidence from animal and human studies suggests that berberine is beneficial for improving lipid profiles, enhancing blood glucose regulation, and combating aging-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, neurological disorders, and type 2 diabetes. Berberine undergoes extensive metabolism in the gut, has notably poor bioavailability, and demonstrates a generally favorable safety profile. Berberine and metformin differ markedly in their chemical structures and bioavailability, but they share many features in terms of their effects on chronic diseases. Furthermore, the two compounds work via many of the same mechanisms, such as activation of AMPK and various cellular energy and antioxidant pathways. Conversely, the mechanisms that drive berberine's lipid-lowering effects, such as regulating various proteins involved in cholesterol metabolism, differ from the mechanisms by which statins work. Although berberine shows promise as a potential therapy for various health conditions, clinical research is needed to confirm the compound's proposed effects in humans.

Related resources

Topics related to Aging

view all-

FOXO

FOXO proteins are transcriptional regulators that play an important role in healthy aging. Some FOXO genes may increase lifespan.

-

Depression

Depression – a neuropsychiatric disorder affecting 322 million people worldwide – is characterized by negative mood and metabolic, hormonal, and immune disturbances.

-

Sirtuins

Sirtuins play a key role in healthspan and longevity by regulating a variety of metabolic processes implicated in aging.

-

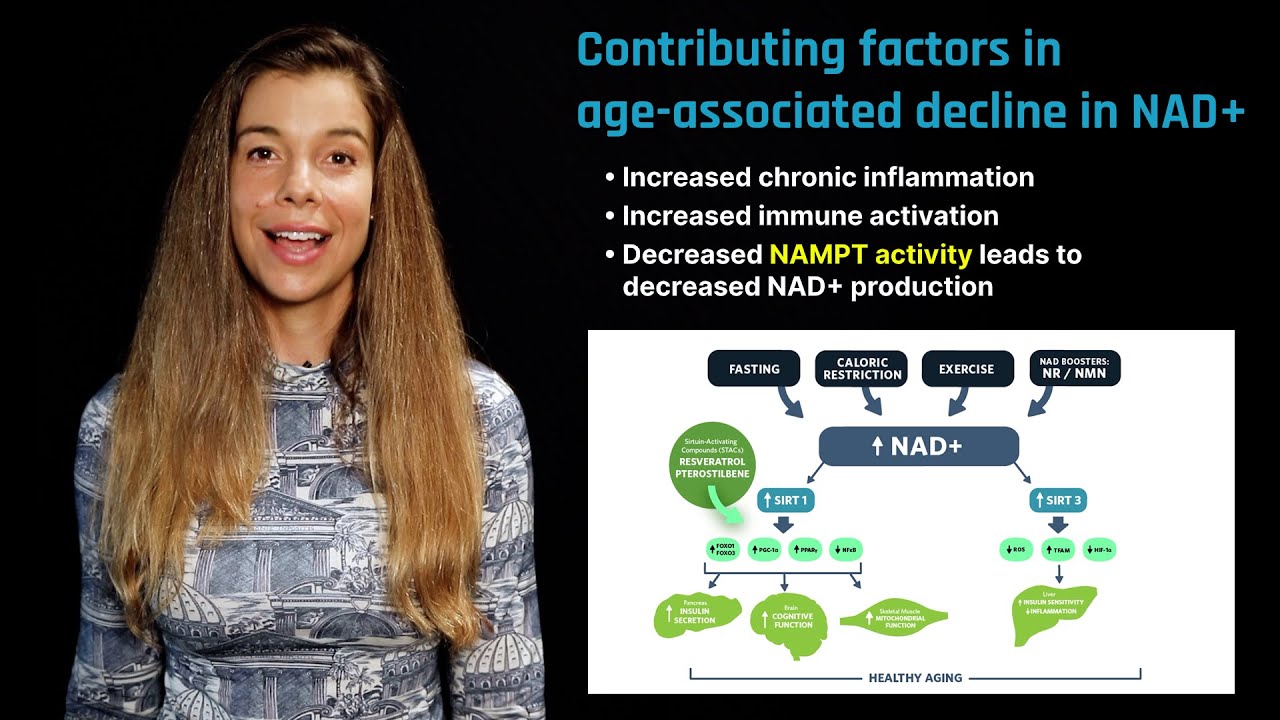

NAD+

NAD+ is a cofactor that plays an essential role in metabolism, DNA repair, and immunity. Its depletion accelerates aging.

-

Nicotinamide riboside

Nicotinamide riboside is a precursor of NAD+, a coenzyme necessary for energy production and cellular repair. It is available from food and supplements.

-

Nicotinamide mononucleotide

Nicotinamide mononucleotide is a precursor of NAD+, a coenzyme necessary for cellular energy production and DNA repair. It is available as a supplement.