What is the optimal source and dose of sulforaphane? | Jed Fahey

Enter your email to get our 15-page guide to sprouting broccoli and learn about the science of chemoprotective compount sulforaphane.

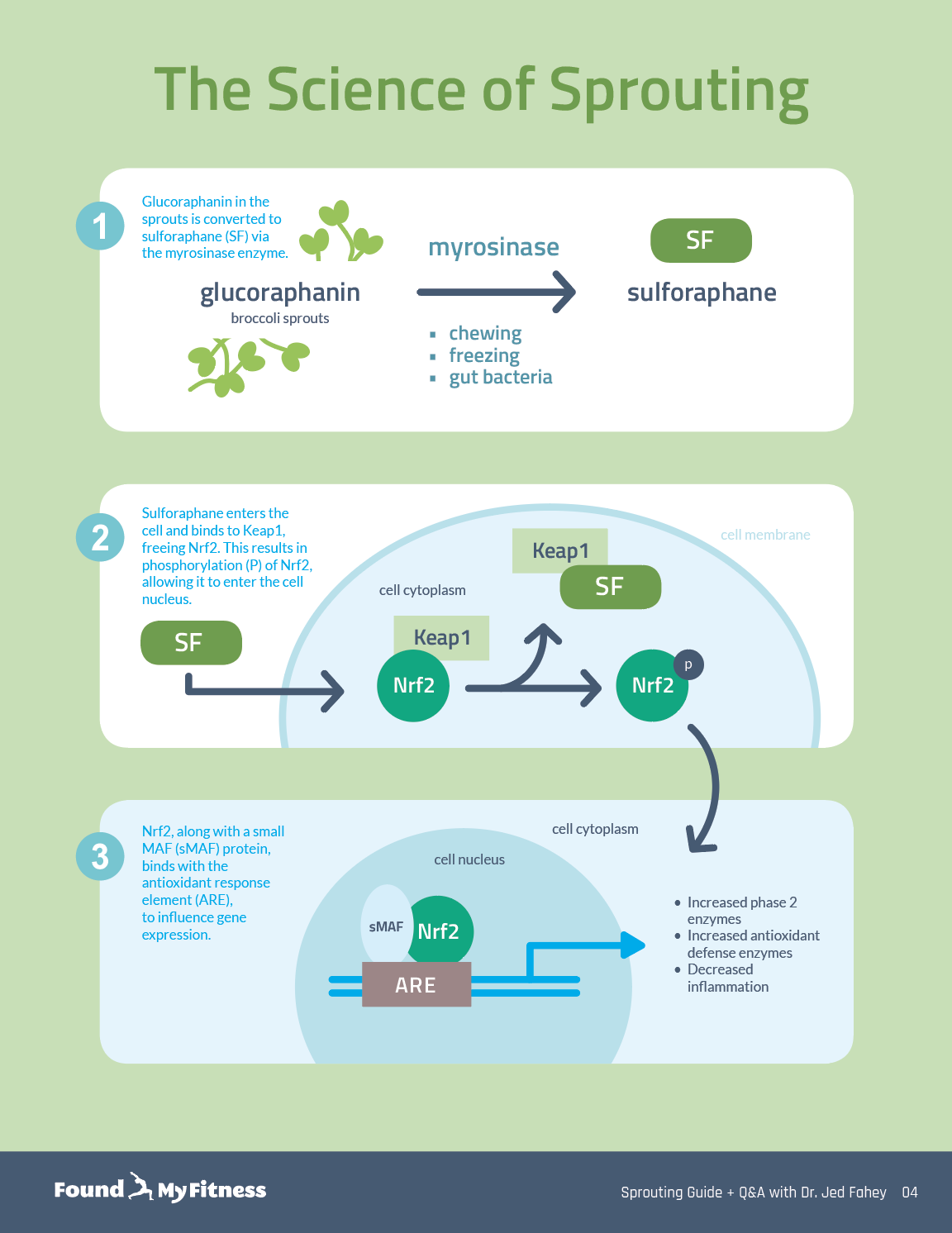

Broccoli sprouts are concentrated sources of sulforaphane, a type of isothiocyanate. Damaging broccoli sprouts – when chewing, chopping, or freezing – triggers an enzymatic reaction in the tiny plants that produces sulforaphane.

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

Sulforaphane is an end-product of a chemical reaction between two compounds present in certain cruciferous vegetables: glucoraphanin and myrosinase, the quantity and activity of which can vary based on a variety of factors. For example, glucoraphanin content differs based on a plant's life stage, cultivar, and growing conditions, and myrosinase, an enzyme, is heat-sensitive and rapidly denatures during normal cooking processes. Workarounds for these problems include eating younger plants (such as broccoli sprouts), adding ground mustard seed (which is rich in myrosinase) to cooked vegetables, or employing shorter cooking times and less water to favor sulforaphane production. A fail-safe mechanism is found in the gut, where commensal bacteria that reside there produce – at varying rates – myrosinase. In this clip, sulforaphane expert Dr. Jed Fahey describes some of the problems that complicate determining the optimal source and dose of sulforaphane.

[Dr. Patrick]: The first question is, "What is the minimum daily dose of sulforaphane that has shown to...that has been shown to provide health benefits? How much sulforaphane does a 200-gram serving of broccoli, or broccoli sprouts, contain?"

[Dr. Fahey]: Yeah, so, you know, I have to preface these, my launching into the answers to some of these questions, by saying, yeah, you went through the extensive and wonderful questions, many of them, as did I, a number of days ago. This is a kind of question that comes up all the time. And to those of you who are non-scientists, I tend to talk...we scientists, and certainly chemists and biochemists, tend to talk in micromoles. So if you look at any of our papers, we talk micromoles. I've... I will try to give you an answer that's translated into milligrams. But this is, of course, complex and something that's still in play and is still being researched by many people.

So it all depends on the amount of glucoraphanin, the precursor of sulforaphane, that is in broccoli, or sprouts. I'm going to avoid a long diatribe on glucoraphanin and myrosinase and sulforaphane because I have the feeling that if you listen to Rhonda at all or gone to our podcast...the podcast that she and I did together or some of her subsequent podcasts, most people know about the fact that glucoraphanin is a precursor found in the plants, myrosinase is an enzyme found in the plants and in your body, your microbiome, and they react and they form sulforaphane.

[Dr. Patrick]: I think that's so interesting, that we have the enzyme in our gut. Meaning we're meant to get the precursor to convert it into sulforaphane. We contain the enzyme in our gut. I just love that. Anyways, go ahead.

[Dr. Fahey]: So absolutely, all of us do. And I mean that, all however many hundred of you there are in this call all have myrosinase-containing bacteria in your gut. Unless you've just blasted yourself with antibiotics and had a...you know, an enema and just cleaned out your intestinal system, then maybe you don't have any. And we've done these sorts of experiments actually with real people.

So there are two ways of doing this, of hydrolyzing the glucoraphanin that's present in broccoli. One is when you chew it, you release the enzyme from the broccoli tissue or broccoli sprouts or broccoli seeds. And the second way is from your microbiome. And if you take supplements, you're either getting just glucoraphanin or there are now supplements with a combination of glucoraphanin and myrosinase. And there are very few, if any, good ones with just sulforaphane. And we'll get to that later, I'm sure, we have to.

So the question was about the dose. And if you're... The best advice that we can give...that I can give now is that all the clinical studies seem to be pointing towards a dose of something between about 50 and 100 micromoles of sulforaphane a day. I discuss that a little bit in the sprouting PDF that Rhonda has just put out. But the question that was originally posted talks about a 200-gram.

So let's start with the question, a 200-gram serving of broccoli. That's a pretty lot for most people, I think. That's a very healthy serving of broccoli, market-stage broccoli. However, broccoli...for broccoli sprouts that's a huge serving. Most people that I'm aware of, including myself, would not enjoy cramming down 200 grams of broccoli sprouts.

So I'll just base a ballpark estimation on 100 grams of either broccoli or sprouts. And based on the amount of glucoraphanin that's in them and our knowledge of conversion in yield, you might get about anywhere between 4 milligrams of glucoraphanin to 100, 150 from 100 grams of broccoli. And that would yield about...anywhere from about half a milligram to something like 18 milligrams of sulforaphane. That's of broccoli.

Why is there a huge range? There's a huge range because, A, all of the broccoli is different, it's different based on the way it's treated in store, the way it's grown, the genetics of the broccoli. And secondly, all of you are different and your gut microbiomes are going to yield different amounts of sulforaphane.

So there's a huge range. And with broccoli sprouts, 100 grams would give you somewhere between, I don't know, about 5 milligrams and 350... Sorry, between about 5 or 6 milligrams and about 60 milligrams of sulforaphane.

So those are just rough approximations. Cooking destroys myrosinase. So if you're cooking broccoli or broccoli sprouts, then you're just counting on the bacteria in your gut. I mentioned the person-to-person variation, there's no way, unfortunately, to know if you're a good converter. There's no way to know how much sulforaphane or glucoraphanin is in broccoli or broccoli sprouts because you have to get them tested in a lab. And there are no commercial labs that do these tests routinely.

So this is still a problem. And, you know, you...I mentioned this in the PDF that Rhonda has posted. But unfortunately you as a consumer are, you know, even if you spend, say, $10 on broccoli seeds and sprout them yourself, it would cost you $150 to send one sample of those broccoli seeds out to a commercial lab to get them tested to see if they're high glucoraphanin or not.

So as I... You know, I don't make the rules, I just abide by them, or try to. But, so unfortunately, as it stands now, it's very difficult to know what you're getting. So we just have to work...we just have to talk in terms of rough averages. And when Paul Talalay and I did our first publication on broccoli sprouts, you know, our point was that a serving of, say, something like a couple of ounces, 60 grams or so, of broccoli sprouts gave you as much glucoraphanin as, you know, a quarter of a pound or a half a pound of market-stage broccoli.

And so these are all... One final word, just that the quantity of glucoraphanin and sulforaphane you get from broccoli sprouts from a couple of ounces we think is a reasonable amount to put you in a zone where you're getting some protective effect. And so it's this...roughly this level that most of the clinical studies have targeted. Because god forbid your clinical studies should be positive and work. You want to be able to translate that to something people can eat.

I think the answers to all the rest of my questions will be shorter, Rhonda. And you've been gracious not to jump in and interrupt, but I hope that sort of addressed the question though.

Any of a group of complex proteins or conjugated proteins that are produced by living cells and act as catalyst in specific biochemical reactions.

A glucosinolate (see definition) found in certain cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and mustard. Glucoraphanin is hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase to produce sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate compound that has many beneficial health effects in humans.

An essential mineral present in many foods. Iron participates in many physiological functions and is a critical component of hemoglobin. Iron deficiency can cause anemia, fatigue, shortness of breath, and heart arrhythmias.

The collection of genomes of the microorganisms in a given niche. The human microbiome plays key roles in development, immunity, and nutrition. Microbiome dysfunction is associated with the pathology of several conditions, including obesity, depression, and autoimmune disorders such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, and fibromyalgia.

A chemical that causes Parkinson's disease-like symptoms. MPTP undergoes enzymatic modification in the brain to form MPP+, a neurotoxic compound that interrupts the electron transport system of dopaminergic neurons. MPTP is chemically related to rotenone and paraquat, pesticides that can produce parkinsonian features in animals.

A family of enzymes whose sole known substrates are glucosinolates. Myrosinase is located in specialized cells within the leaves, stems, and flowers of cruciferous plants. When the plant is damaged by insects or eaten by humans, the myrosinase is released and subsequently hydrolyzes nearby glucosinolate compounds to form isothiocyanates (see definition), which demonstrate many beneficial health effects in humans. Microbes in the human gut also produce myrosinase and can convert non-hydrolyzed glucosinolates to isothiocyanates.

An isothiocyanate compound derived from cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and mustard. Sulforaphane is produced when the plant is damaged when attacked by insects or eaten by humans. It activates cytoprotective mechanisms within cells in a hormetic-type response. Sulforaphane has demonstrated beneficial effects against several chronic health conditions, including autism, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and others.

Get email updates with the latest curated healthspan research

Support our work

Every other week premium members receive a special edition newsletter that summarizes all of the latest healthspan research.

Sulforaphane News

- Broccoli seed extract with a sulforaphane precursor reduced common cold symptom days in healthy adults.

- Sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extract modestly lowers fasting blood sugar in some people with prediabetes, perhaps due to variations in gut microbiota and individual metabolic traits.

- Sulforaphane, derived from broccoli, activates Nrf2, mitigating age-related skin changes and boosting the antioxidant defense system in mice.

- Sulforaphane from broccoli sprouts shows promise in preventing Alzheimer's disease – boosting memory and enhancing mitochondrial function in mice.

- Breathwork enhances endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity to counter oxidative stress.