How long does it take for glucoraphanin to convert to sulforaphane? | Jed Fahey

Enter your email to get our 15-page guide to sprouting broccoli and learn about the science of chemoprotective compount sulforaphane.

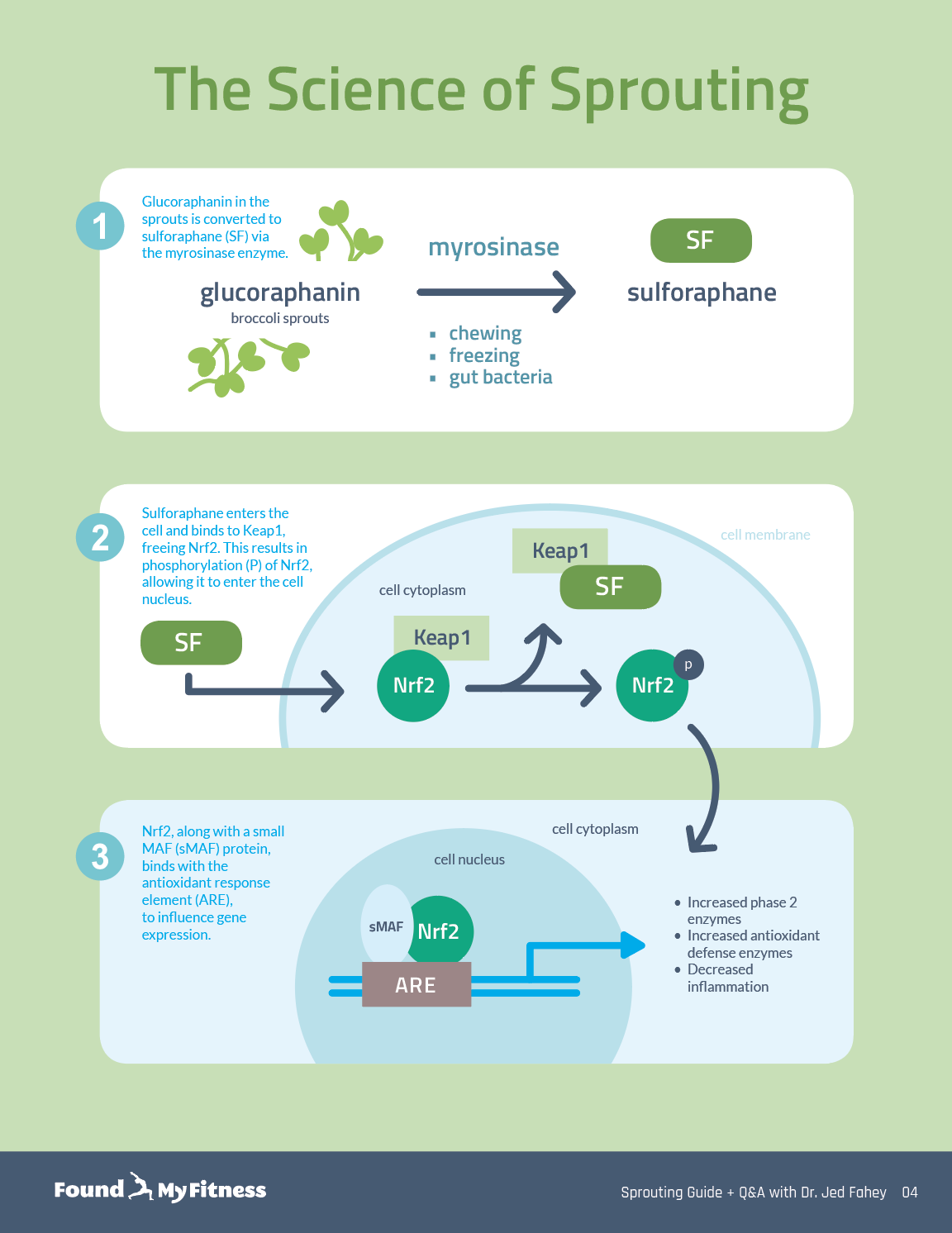

Broccoli sprouts are concentrated sources of sulforaphane, a type of isothiocyanate. Damaging broccoli sprouts – when chewing, chopping, or freezing – triggers an enzymatic reaction in the tiny plants that produces sulforaphane.

Get the full length version of this episode as a podcast.

This episode will make a great companion for a long drive.

Glucosinolates are mildly flavored compounds found in the stems, leaves, and seeds of cruciferous plants. They coexist with but are compartmentally segregated from plant myrosinases, an endogenous family of enzymes whose sole known substrates are glucosinolates. When cruciferous plants are crushed or damaged by insect attack or human consumption, the myrosinases hydrolyze the glucosinolates to yield a variety of degradation products, including isothiocyanate compounds. Isothiocyanates lend a pungent aroma and sharp flavor (sometimes described as “bitter”) to these plants and are responsible for the “heat” commonly associated with wasabi and horseradish. Although the reaction begins immediately, full hydrolysis can take several minutes. In this clip, Dr. Jed Fahey describes the chemical reaction that produces isothiocyanates and the time frame required for full conversion.

Rhonda: I've noticed when I've made my broccoli sprout smoothie, after blending it, if I let it sit in my cup for a prolonged period of time, it tastes different, like there is...and I don't know if that's the sulforaphane or the sulforaphane nitriles or what chemical reaction is going on there. But it tastes different than if I just blend it up and drink it immediately.

Jed: I think it's probably the sulforaphane. So when you blend it and drink it immediately, you probably haven't given enough time for all of the glucosinolates to be converted to sulforaphane.

Rhonda: Do you have any idea how long, what the temporal sort of timeline in minutes?

Jed: Probably a couple of minutes to, yeah... I mean, so when we did these conversions in big vats, 600... I think there were 600...no, 200 or 300-gallon steam kettles at Oregon Freeze Dry, we added daikon sprouts, homogenized and let the stew sit for 2 hours to get complete hydrolysis. You can do the calculation of sort of the half-life of the enzyme and how fast it works. And so it certainly, it takes a matter of many minutes. So in your particular case, with your broccoli sprouts, maybe it was 10 minutes or maybe it takes a half hour to get completely converted.

So probably what you were doing is chugging the not-so-nasty-tasting glucosinolates.

Rhonda: It does get more foul-tasting, as you had said, It does.

Jed: Yeah, exactly. And so the conversion is happening on the way down the tubes and then, when it gets to your intestines, probably more happens. And I should mention, speaking of intestines, we have no idea where most of the myrosinase activity is. Most of the bacteria in your guts are in your large intestine. But I wouldn't rule out the fact that a fair amount of conversion occurs in the small intestine, too.

Rhonda: Really?

Jed: Yeah. And I say that based on the fact on the pharmacokinetics that we see because we know that...we see the metabolites of sulforaphane occur, appear in the blood within 10 minutes of ingestion.

Rhonda: That's pretty fast.

Jed: And when you talk to a gastroenterologist about gut transit time, it stands to reason that it takes more than 10 minutes to get, or 15 minutes, to get all the way to your large intestine and undergo a chemical reaction. So, of course, it's very difficult to access the small intestine of a person, experimentally. It's been done, but...

Rhonda: Do you know how long? So, for example, if I drink my broccoli sprout on Monday, I'm going to activate Nrf2 while I have some of these metabolites glutathione, things like that. How long does that reaction occur before then? Like, so I've been taking this broccoli smoothie when we're not traveling and we're home. We're getting it, like, probably five days a week. You know, do you have to take it every day or do you think that's sort of overkill? Does it last longer? Do you have any idea?

Jed: I think you are perfectly healthy. You're good. No, I think you should be fine. Again, we don't know enough, but it's apparent certainly in animal systems and in the limited number of cases where it's been looked at in people. It's not like taking a drug. It's not like taking an aspirin, which is going to be flushed from your system and the pharmacokinetics look like this and they are there, it appears, its metabolites appear and it's gone. What you are doing when you take sulforaphane is you're up-regulating a bunch of enzymes. And those enzymes have a rather long, comparatively, a rather long half-life meaning they don't lose their punch. They don't get deactivated or get broken down all that fast. And their half-lives are on the order of days, maybe even weeks for some of them, but certainly a few days is a reasonable guess for many of them. So once you boost all these enzymes, they stay up-regulated, in other words, more active for a period of time and then it goes away.

Any of a group of complex proteins or conjugated proteins that are produced by living cells and act as catalyst in specific biochemical reactions.

A glucosinolate (see definition) found in certain cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and mustard. Glucoraphanin is hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase to produce sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate compound that has many beneficial health effects in humans.

Plant secondary metabolites found primarily in cruciferous vegetables. Glucosinolates give rise to a variety of compounds that have been identified as potent chemoprotective agents in humans against the pathogenesis of many chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disease, among others. These products are responsible for the pungent aroma, sharp flavor, and the “heat” commonly associated with some cruciferous vegetables such as wasabi and horseradish.

An antioxidant compound produced by the body’s cells. Glutathione helps prevent damage from oxidative stress caused by the production of reactive oxygen species.

A family of enzymes whose sole known substrates are glucosinolates. Myrosinase is located in specialized cells within the leaves, stems, and flowers of cruciferous plants. When the plant is damaged by insects or eaten by humans, the myrosinase is released and subsequently hydrolyzes nearby glucosinolate compounds to form isothiocyanates (see definition), which demonstrate many beneficial health effects in humans. Microbes in the human gut also produce myrosinase and can convert non-hydrolyzed glucosinolates to isothiocyanates.

A protein typically present in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells. Nrf2 can relocate to the nucleus where it regulates the expression of hundreds of antioxidant and stress response proteins that protect against oxidative damage triggered by injury and inflammation. One of the most well-known naturally-occurring inducers of Nrf2 is sulforaphane, a compound derived from cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli.

The movement of a drug or other xenobiotic substance into, through, and out of the body. Pharmacokinetics comprises absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, often abbreviated "ADME." Many factors influence pharmacokinetics, including a person's age, gut health, and circadian rhythms, as well as the substance's bioavailability.

An isothiocyanate compound derived from cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and mustard. Sulforaphane is produced when the plant is damaged when attacked by insects or eaten by humans. It activates cytoprotective mechanisms within cells in a hormetic-type response. Sulforaphane has demonstrated beneficial effects against several chronic health conditions, including autism, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and others.

Get email updates with the latest curated healthspan research

Support our work

Every other week premium members receive a special edition newsletter that summarizes all of the latest healthspan research.

Sulforaphane News

- Broccoli seed extract with a sulforaphane precursor reduced common cold symptom days in healthy adults.

- Sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extract modestly lowers fasting blood sugar in some people with prediabetes, perhaps due to variations in gut microbiota and individual metabolic traits.

- Sulforaphane, derived from broccoli, activates Nrf2, mitigating age-related skin changes and boosting the antioxidant defense system in mice.

- Sulforaphane from broccoli sprouts shows promise in preventing Alzheimer's disease – boosting memory and enhancing mitochondrial function in mice.

- Breathwork enhances endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity to counter oxidative stress.